Two Exhibitions Chart Judy Chicago’s Visionary Legacy

Major surveys at the Serpentine Galleries, London, and the LUMA Foundation, Arles, celebrate the artist's enduring dedication to feminist practice and social justice

Major surveys at the Serpentine Galleries, London, and the LUMA Foundation, Arles, celebrate the artist's enduring dedication to feminist practice and social justice

A small watercolour caught my eye at the entrance to ‘Herstory’, Judy Chicago’s current survey at the LUMA Foundation, Arles. In this drawing, part of the 140-work series ‘Autobiography of a Year (1993–94)’, a crudely rendered woman is about to be hit on the head by a man holding a mallet. An accusation in a mix of loopy cursive and capital letters encloses her from above and below. ‘You make BAD ART,’ the text reads. ‘IT HURTS.’

While he may not have held a mallet over Chicago’s head, the critic Hilton Kramer must have caused real offence to the artist when he asked in his New York Times review of her eponymous 1980 show at the Brooklyn Museum: ‘Is The Dinner Party even art?’ Before concluding that, even if it was art, it was bad art. Of course, Chicago had the last laugh. The Dinner Party (1974–79), a ceremonial banquet table set with plates dedicated to influential women throughout history, is now permanently installed in its own room of the museum.

The inclusion of ‘Autobiography of a Year (1993–94)’ strikes a curious tone in an otherwise celebratory exhibition, which originated at the New Museum, New York, and opened at LUMA a month after another survey show, ‘Revelations’, at Serpentine Galleries, London. Together, the attention generated by both exhibitions, which feature examples from all Chicago’s major bodies of work in mostly chronological order, constitutes something of a victory lap for the 85-year-old artist. But by opening with a series that centres on self-doubt and anxiety, Chicago reminds audiences that her success did not come overnight. Rather, it took six decades until she finally got the full recognition that she always felt she deserved.

Born into a progressive Jewish family in 1939, Chicago, whose adopted surname is assumed from her native city, has said that she felt ‘entitled’ to become an artist, but that her ambitions collided with the societal construction of femininity. One of the earliest works on display in Arles, Rainbow Pickett (1965/2004), embodies this tension, reimagining the minimalist sculpture of the era in a candy-hued palette. Comprising six monochrome trapezoids leant against the wall in decreasing size order, it looks, in the best way possible, like what might have happened if John McCracken had produced a sculpture for the Barbie Dreamhouse.

Rainbow Pickett is flanked by two wall-based works from Chicago’s ‘Hoods’ series (1964–65), created while the artist was enrolled in an autobody school, where she was the only woman in a group of 250 men. They combine that great totem of masculinity, the car – or, more specifically, its bonnet – with organic shapes reminiscent of the vulva, rendered in acrylic lacquer in a variety of jewel tones. The wall text for the series states that the artist’s ‘use of expressive colour led to accusation from some critics that a work was “too feminine”’. I can only imagine this is polite understatement.

Still, Chicago doubled down, producing several series of abstract paintings in the late 1960s and early ’70s, which played with gradient and contrast to widen the visual vocabulary of minimalism and communicate ‘the “dissolving sensation” of the female orgasm’, according to the exhibition materials. At Serpentine, a section of the show is dedicated to preparatory drawings for some of these series, including ‘Pasadena Lifesavers’ (1969–70) and ‘Flesh Gardens’ (1971), highlighting the exhibition’s focus on Chicago’s drawings. For fans, it’s a delight to see these lesser-exhibited, small-scale works, but they are no substitute for the luminosity and exacting finish of the paintings on display in ‘Herstory’.

In the ‘Revelations’ catalogue, Chicago recounts how, as an undergraduate at the University of California, she took a class titled ‘The Intellectual History of Europe’. She waited all semester for the professor’s promised lecture on women’s contributions and was dismayed when he announced in the final meeting that they hadn’t made any. From the mid-1970s, Chicago orientated her practice towards disproving this theory. She started to piece together her own timeline of significant mythical and historical women, poring over out-of-print books bought in secondhand shops ‘for one dollar, as no one was interested in women’s history then’.

In 1979, her labour finally came to fruition in The Dinner Party. The work poses a dilemma for would-be curators of a Chicago retrospective: How to stage a survey of an artist’s practice when the one piece everyone knows cannot be included? In both Arles and London, the solution is to present a section dedicated to the work’s preparatory line drawings, documentary videos and installation views alongside a number of the famous vulva plates. It does the job but doesn’t come near the awe-inducing experience of seeing the work in its entirety.

If ‘Herstory’ and ‘Revelations’ have a mission statement, though, it’s to prove that Chicago is more than just a one-hit wonder. Her contributions to the field of feminist ecology are on full display in these shows, from the photographs of her performance series ‘Atmospheres’ (1968–74) – in which she created elaborate spectacles in the southern Californian landscape with smoke machines, fireworks and flairs – to later drawings focused on animal rights and environmental protection (Extinction Relief, 2018, and Orphaned Tree, 1993). The inclusion of the latter works draws a direct link between the oppression of women and non-human entities, suggesting their liberation is interrelated, a key tenant of ecofeminism.

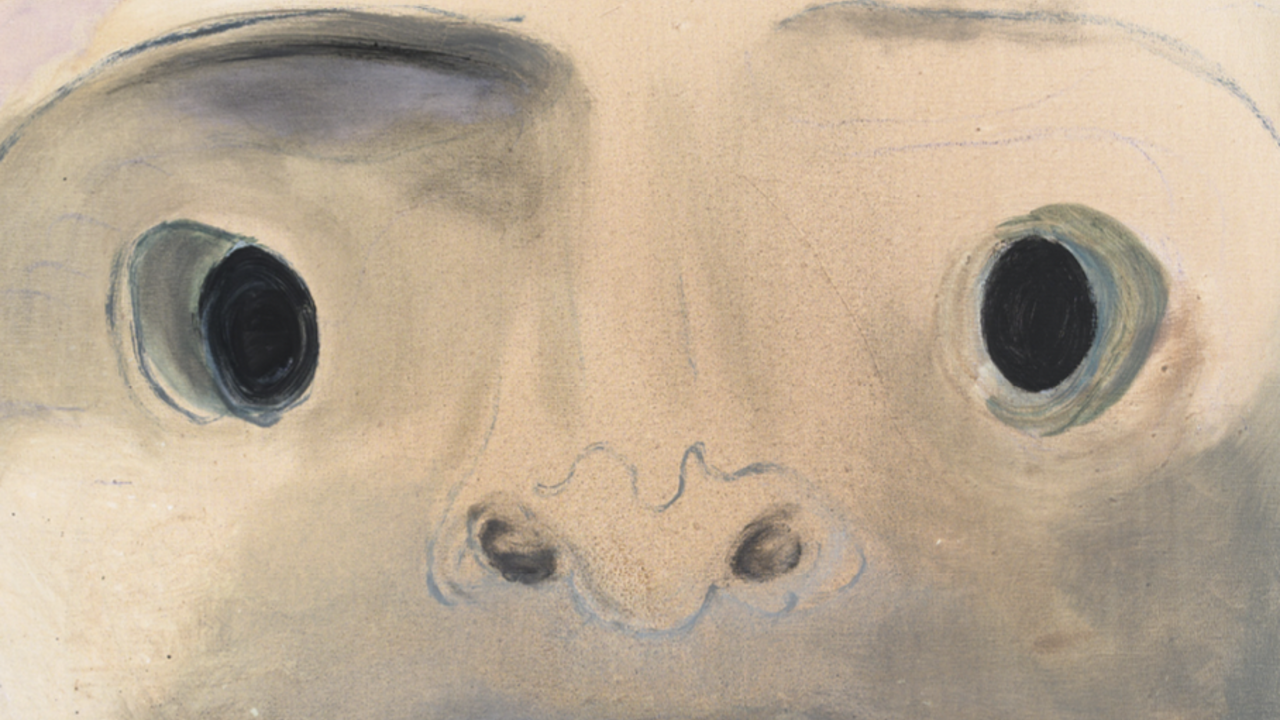

The exhibitions’ real highlights, though, are the selections from Chicago’s painting and needlework series, ‘Birth Project’ (1980–85). As with her early paintings, the impetus to start the project stemmed from the systemic lack of images devoted to women’s lived experiences: in this case, the act of bringing life into the world. In the exquisite Birth Trinity: Needlepoint 1 (1983), on view in Arles, the female body is depicted as a mountainous landscape surrounded by zig-zagging rays of sunlight. A baby in the bottom left-hand corner of the canvas seems to have shot out from between the woman’s open legs, leaving contrails in its wake. In other works, such as In the Beginning (1980), on display in London, Chicago reimagines the Genesis myth with a female God. By tying women’s bodies to nature and the world’s creation, Chicago’s visions insist that birth is a universal human experience and reproductive rights impact everyone.

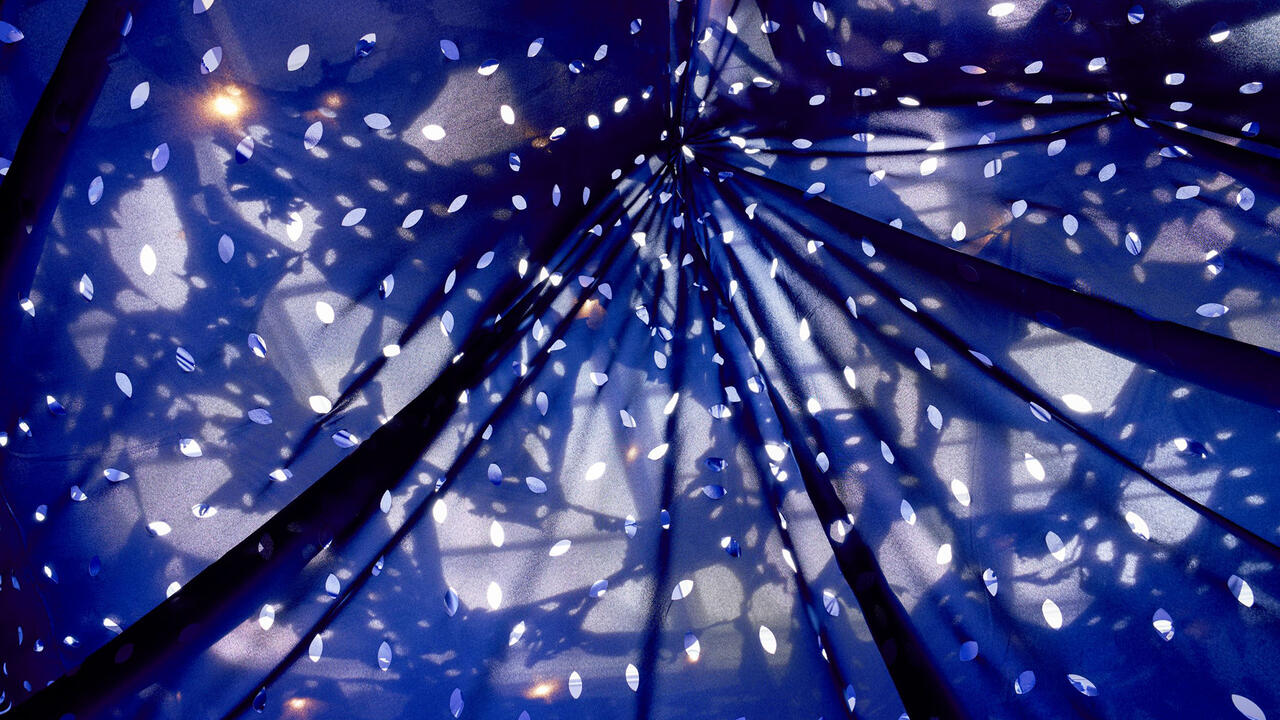

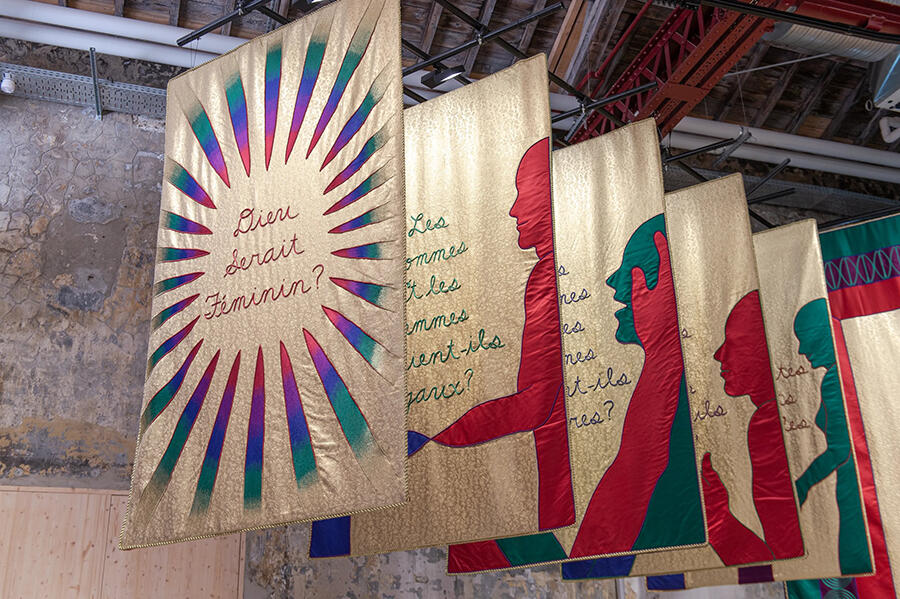

‘Herstory’ closes with Chicago’s most recent projects, What if Women Ruled the World? (2020), 21 embroidered fabric banners produced by women at the Chanakya School of Craft in Mumbai. Originally hung inside The Female Divine (2020) – a monumental inflatable architectural installation shaped like a palaeolithic goddess, which Chicago realized for the Dior Spring-Summer 2020 Haute Couture runway show in Paris – the banners pose queries related to the titular question, such as ‘Would there be violence?’ and ‘Would life be protected?’ Given the space dedicated to these works at LUMA, it’s clear the curators intended the installation as the exhibition’s pièce de résistance, but such over-simplistic musings strike me as naive in an era in which female politicians are often just as hawkish as their male colleagues.

A more fitting ending would have been ‘Mortality Relief’ (2019), a group of drawings on black glass in which Chicago contemplates her own death. Each panel answers the question ‘How Will I Die?’ with answers ranging from ‘Will I die in my own bed with my cat by my side?’ to ‘No one wants to die hooked up to machines in a hospital.’ All her life, Chicago has been a self-described ‘troublemaker’, consistently saying what people didn’t want her to say and producing work considered socially progressive. It feels fitting that an artist who has long sought to create representations missing from art history, would confront the rarely seen ageing female subject in the twilight of her career.

Judy Chicago’s ‘Herstory’ is at LUMA Arles until 29 September, and ‘Revelations’ is at Serpentine North Gallery, London, until 01 September

Main image: Judy Chicago, Birth Trinity from the ‘Birth Project’ (detail), 1983, needlepoint on canvas. Needlework by Susan Bloomenstein, Elizabeth Colten, Karen Fogel, Helene Hirmes, Bernice Levitt, Linda Rothenberg and Miriam Vogelman, 1.3 × 3.3 m. Courtesy: The Gusford Collection © ADAGP, Paris, 2024 © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York